Pretend and Extend, Redux

Several months ago I wrote an article about a banking phenomenon which goes by various names, but which I called Pretend and Extend.

It goes like this. If I am a banker and I have a bad loan on my books (none of the bankers we know are in this group, so let’s assume we are talking about a New York banker) it is time to classify it, write it down, and move on.

Only, if I do that, I impair my capital, and if I do that enough, I have to raise capital to cure the impairment.

So, I don’t want to write them off.

In the mean time, economic confidence is tricky. If I and my fellow bankers begin dumping assets on the market, not only will the overall price level of assets go down, but people’s confidence in the economy will go down, perhaps creating a self-reinforcing, downward spiral.

And, maybe the economy will improve so that some or all of these loans will recover their performing status.

So, the government and the regulators don’t want me to write it off.

We all just leave the loan on our books and pretend it is a good loan. We urge the borrower to take the loan somewhere else, knowing that there is no place to go. We might even threaten calling the loan. But in the end, we extend the loan.

We Pretend and Extend, with the regulators’ blessing. In particular there appears to be a concerted effort to keep as many residences off the market as possible so as to keep housing prices as high as possible so as to prop up the economy to the extent it can be propped up. Analyst Meredith Whitney put it this way, “What has kept home prices stable … (is that) there’s been a ton of inventory kept from the market. So, if you control the supply, you can control the price without controlling the demand.”

When I first heard of Pretend and Extend, the rules were informal (although there was some formal guidance from regulators instructing banks not to take action on certain real estate loans), but the loans in question generally needed to be at least current on interest payments.

No more. Many banks are Pretending and Extending “as long as it is good business.”

The end result is a continuing virtual overhang of trillions of dollars of toxic assets and other loans that will have to be dealt with eventually.

Hopefully, “eventually” will include a more robust economy.

So, how goes the banking sector these days, aside from creative balance sheet and capital accounting?

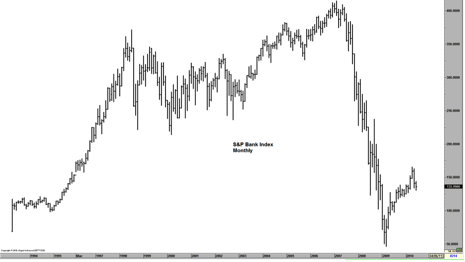

This chart of the S&P Bank Index illustrates the terrifying decline in the index of 89% from 2007 – 2009. Coincidentally, the Dow Jones Industrial Index lost 89% of its value from 1929 – 1932 in the Great Depression. The index has recovered, currently having lost 67% of its value from the peak. The shallow recovery indicates that all is not well. (By comparison, the Dow Jones Industrial Average, which, at its low, lost “only” 50% of its value, is now at the point at which it has lost approximately 40% of its value from the peak.)

Although banks have been reporting sometimes-record earnings due primarily to low cost of funds (Whitney again: “I would say a vast majority of the banking sector’s profits and capital creation (in 2009) was government induced. In the first quarter (of 2010), it’s highly arguable that certain companies wrote up assets.”), several factors have led to caution when thinking about banks’ longer term prospects, including:

- Continued high levels of toxic assets on balance sheets (Whitney: “If you look at nonperforming assets (for the top 4 banks), … the size of that is 1.5 times all of the charge-offs that banks have incurred since 2005.”)

- The specter of financial reform’s impact on earnings

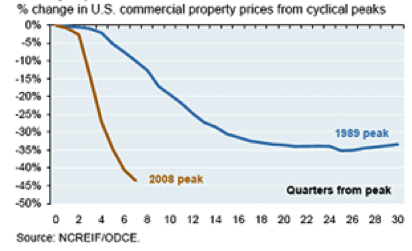

- Concern that the housing market will take another fall following the end of the home buyers’ tax credit, and that commercial real estate prices have not yet found a bottom.

http://paul.kedrosky.com/archives/2010/03/the_case_for_co.html

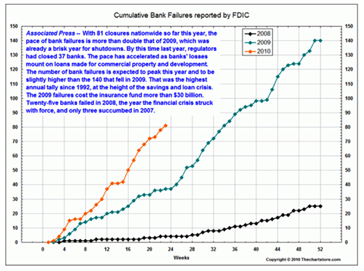

In addition, in spite of Pretend and Extend, banks continue to fail at a post-Depression record rate, with 140 failures in 2009 and 80 through June 4, 2010.

The FDIC says that there were 775 “problem banks,” having $431 billion of assets, at the end of the first quarter of 2010, compared with 305 banks, having $220 billion of assets, at the end of the first quarter of 2009.

Clearly, the trend remains in the wrong direction.

It is likely that a good sign of a durable bottom will be when banks and regulators have enough confidence to begin to dismantle Pretend and Extend.